The survival of alpine ski resorts? Increase their density says PhD student, Fiona Pià

Winter resorts in the mountains will need to increase their density to prevent their decline, according to a PhD thesis in architecture.

PhD student Fiona Pià offers concrete and innovative solutions for Verbier, a typical example of the problems that winter resorts face today (including Crans Montana and Zermatt).

Some Swiss ski resorts are reaching a point of saturation, with peak-time traffic jams, new buildings popping up in avalanche zones, and general encroachment upon the natural surroundings. While the current trend is to stop construction [following the Lex Weber], an EPFL doctoral thesis suggests that the opposite might be necessary: we need to invest in these regions, increase their density, and ensure seamless public transportation to and from them.

At the Architecture and Urban Mobility Laboratory (LAMU), Fiona Pià, from the Principality of Andorra, studied and compared the challenges faced by the Swiss resorts Verbier, Zermatt, and Andermatt Swiss Alps, as well as France's Avoriaz and Canada's Whistler-Blackcomb. Her thesis highlights the persistent myth of an isolated chalet surrounded by nature and claims that this idyllic image is responsible for the saturation of alpine towns. Using Verbier as an example, Pià puts forward a series of solutions to safeguard the future of this Valais resort while at the same time preserving its natural environment.

Q: You began your PhD in architecture just before the Lex Weber was passed on 11 March 2012, which limited construction of new second homes to 20%. What do you think the outcome will be for the Alps?

The [Lex Weber] initiative made the public aware of the need to slow the urban sprawl encroaching upon the alpine landscape. But unfortunately the only solution was to criticize the economic model of having a second home. The images from the 2012 campaign highlighted the issue using ambiguous communication ploys that stigmatized dense construction and the urbanization of mountain resorts. But the campaign oversimplified matters. "Density" became something that was harmful to nature and created ugliness, while "urbanization" was responsible for the sprawl encroaching upon the landscape. Yet the problems alpine towns face are caused by their low density, which results from the growing number of single chalets. Nobody dares to criticize this model, considered so idyllic. But it should be condemned because it is just this model that leads to urban sprawl and encourages people to use their cars. Yet Franz Weber presented it as the ideal: the poster thanking people for accepting the initiative showed Zermatt with an isolated chalet below the Matterhorn, claiming that by stopping all new construction we could return to this alpine "authenticity". Weber's remarkable paradox can be summed up as follows: he accepts that urban sprawl exists and condemns it, yet, at the same time, he glorifies the same urban model that caused it and absolves it of all blame.

Q: So how can we escape this paradox?

Q: So how can we escape this paradox?

We can't maintain this false impression. The [Lex Weber] initiative's implicit goal of keeping the status quo will not simply make the large alpine towns above 1,400m altitude disappear. Instead of trying to go back to how things were, which is impossible, it would be better to focus on the serious problem of urban saturation and the climate issues that these regions face today. Unless we increase the density of these towns over the long term, they will quite simply fall into decline, and the consequences for the "unspoiled" nature nearby would be catastrophic. The [Lex Weber] initiative ignores this aspect, which is nevertheless essential for protecting the alpine landscape.

Q: You used Verbier as a case study. What would you recommend to that resort in terms of future development?

To solve the traffic problems, the municipality of Bagnes plans to build two new ring roads, one of which will run through an avalanche red zone. They will further encroach upon the landscape by building more housing on the almost untouched hillsides in Bruson, which will require more new infrastructure. Yet Verbier already has numerous roads and other infrastructure. It would be better to increase the density of the resort to extend its "lifecycle" and avoid colonizing untouched areas. Q: How could the density be increased?

Q: How could the density be increased?

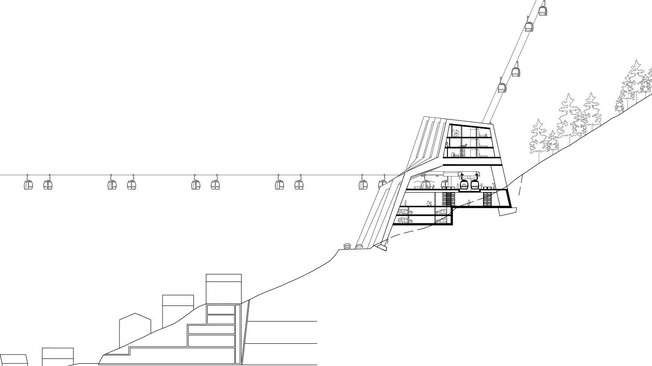

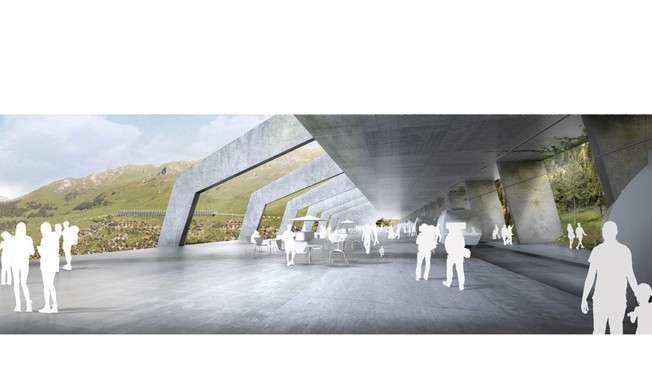

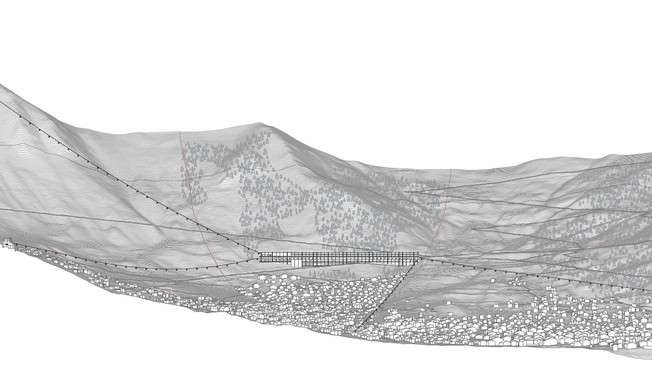

10% of public building land is still available. Based on this, I developed a new urban model that brings together housing and public transport. The aim is to resolve current mobility problems caused by everyone using their cars and rationalize how the last plots of land are used. I recommend building 5 cable-car stations as infrastructure that could be up to 500m long. This would be a new type of building that contains housing, real pedestrian areas – often missing in the mountains – public facilities, and transport interfaces. The inhabited infrastructures would have a density of 1.7 compared to 0.3 for a single chalet and would take up 6x less land than a chalet. This model would add 250,000m2 to the 963,000m2 of existing accommodation, without increasing the urban sprawl on the alpine landscape. An expanded cable-car network could sustainably serve the whole of Verbier without people having to use their cars. I found this form of public transport to be the most appropriate because it's eco-friendly, relatively quiet and cheap, and it is suited to the alpine terrain while taking up very little land. And it allows people to enjoy the alpine scenery. Q: So we have to give up our dream of a mountain chalet, but how do you convince people to live in this kind of infrastructure?

Q: So we have to give up our dream of a mountain chalet, but how do you convince people to live in this kind of infrastructure?

Inhabited infrastructures meet two requirements that a chalet cannot: that of being able to live in the open air and be at one with nature – without destroying it. We may think that chalets are a part of nature but in fact they just swallow it up. Inhabited infrastructures occupy the land in a rational way and can therefore help us to control our footprint on the natural environment. And it will be through green mobility and respect for natural dangers that we will be able to preserve the unspoiled environment over the long term. What's more, these buildings offer a new way of living at altitude. Without leaving the infrastructure, you can go directly from the cable car to your home or to see a concert at the Verbier Festival, go skiing, go for a drink along the pedestrian area in the middle of the building. Then you can take the cable car over the landscape to go to the market in Verbier village, take a class at the international school or go back down into the valley. There's no need for a car, so you get to breathe the alpine air.

Q: Why is this project so relevant for Verbier?

The project is not just about Verbier as a ski resort. It looks ahead to what Verbier will become: an extension of the "real" town that is at one with the natural environment at altitude. The municipality of Bagnes intends to draw visitors ten months of the year by 2035. So the future of Verbier's natural environment is being decided today.

More information: Fiona Pià, "Developing the Swiss Alps: strategies to increase the density of high-altitude towns", supervised by Inès Lamunière, Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Mobility (LAMU).

Provided by: Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne

Read more at: http://phys.org/news/2016-11-alps-chalets.html#jCp